Moral Relativism: Differentiating Good And Evil

Morals are understood as a set of norms, beliefs, values and customs that guide people’s behavior (Stanford University, 2011). Morality is what determines what is right and what is wrong and will allow us to discriminate which actions or thoughts are right or proper and which are not. However, something that seems so obvious on paper raises doubts as we begin to delve into the issue. An answer to these doubts and the apparent contradictions they provoke is what is called moral relativism.

Morality is neither objective nor universal. Within the same culture, we can find differences in morality, even if they are usually smaller than those we find between different cultures. So, if we compare the morals of two cultures, these differences can turn out to be much greater. Furthermore, within the same society, the coexistence of various religions can also show many differences (Rachels and Rachels, 2011).

The concept of ethics is closely related to the concept of morals. Ethics (Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy) is the search for universal principles of morality (although some authors, such as Gustavo Bueno, consider that ethics and morality are the same thing).

For this, those who study ethics analyze morality in different cultures in order to find things in common, which would be universal principles. In the world, ethical behavior is officially established in the declaration of human rights.

western morals

Years ago, Nietzsche (1996) labeled Western morality as slave morality, since this morality considered that the highest actions could not be the work of men, but of a God projected outside of us. This morality, which Nietzsche avoided, is considered Judeo-Christian for its origins.

Despite philosophers’ criticisms, this morality remains in force, even with some more liberal changes. Given colonialism and the domination of the West in the world, Judeo-Christian morality is the most widespread. This fact can sometimes cause problems.

This thought that considers that every culture has a moral is called cultural relativism. Thus, there are people who reject human rights in favor of other codes of good behavior, such as the Koran or the Vedas of the Hindu culture (Santos, 2002).

cultural relativism

Analyzing other morals from the point of view of our morals can be a totalizing practice. Normally, when acting in this way, the assessment tends to be negative and stereotyped. Therefore, we will almost always reject morals that do not fit ours, even questioning the moral abilities of people who have another morality.

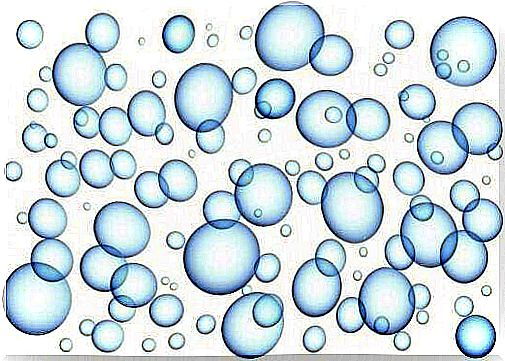

To understand how different morals interact, let’s look at Wittgenstein’s (1989) explanations. He explains the morals with a very simple outline. To understand better, it is possible to perform a simple exercise: take a sheet and randomly draw several circles. Each circle will represent a different morality. With regard to the relationships between the circles, there are three possibilities:

- There are no common spaces between the circles.

- A circle is located within another circle.

- Two circles share a part of your space, but not all.

Evidently, the fact that two circles share the same space will indicate that two morals have aspects in common. Also, depending on the proportion of shared space, they will have more or less things in common. Like some circles, different morals overlap, while they diverge on many positions. There are also larger circles, which represent morals that have more norms, and smaller ones, which only refer to more specific aspects.

moral relativism

However, there is another paradigm that proposes that there is no morality in every culture. Moral relativism proposes that each person has a different morality (Lukes, 2011). Imagine that each circle in the previous scheme is a person’s morals rather than a culture’s morals. From this point of view, all morals are accepted, regardless of place of origin and context. Within cultural relativism there are three different positions:

- Descriptive moral relativism (Swoyer, 2003): this perspective defines that there are divergences in relation to behaviors considered correct, even when the consequences of such behaviors are the same. Descriptive relativists do not necessarily advocate tolerating any behavior in light of such disagreements.

- Meta-ethical moral relativism (Gowans, 2015): according to this perspective, the truth or falsity of a judgment is not the same universally, thus it cannot be said to be objective. Judgments will be relative to being compared with the traditions, beliefs, beliefs or practices of a human community.

- Normative moral relativism (Swoyer, 2003): from this perspective, it is understood that there are no universal moral standards. Therefore, it is not possible to judge people. All behavior must be tolerated, even when it is contrary to our beliefs.

The fact that a moral explains a greater range of behaviors or that more people agree with a specific moral does not imply that it is correct, but neither does it define it as incorrect. Moral relativism assumes that there are several morals that will give rise to divergences, which will not give rise to conflict only when there is dialogue and understanding (Santos, 2002). Thus, finding commonalities is the best way to establish a healthy relationship, both between people and cultures.

Bibliography

Gowans, C. (2015). Moral relativism. Stanford University. Link: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/moral-relativism/#ForArg

Internet encyclopedia of philosophy. Link: http://www.iep.utm.edu/ethics

Lukes, S. (2011). Moral relativism. Barcelona: Paidós.

Nietzsche, FW (1996). The genealogy of morals. Madrid: Editorial Alliance.

Rachels, J. Rachels, S. (2011). The elements of moral philosophy. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Santos, BS (2002). There is a multicultural conception of human rights. El Otro Derecho, (28), 59-83.

Stanford University (2011). “The definition of morality”. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Palo Alto: Stanford University.

Swoyer, C. (2003). Relativism Stanford University. Link: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/relativism/#1.2

Wittgenstein, L. (1989). Conference on Ethics. Barcelona: Paidós.