Anterograde Amnesia: The Inability To Learn

Remembering a phone number when you don’t have your address book, recognizing a person you know on the street and knowing their name, remembering where we went on vacation last year… All of these functions are usually attributed to a very important basic psychological process : the memory. However, when the ability to remember things from the past is impaired or when we are not able to learn something new, it may be that our memory is impaired and we are victims of anterograde amnesia. Let’s delve deeper into this subject.

Today, the role of memory is also important due to the time we save when it is in good working order. Thus, people with “a good memory” are able to solve a problem more quickly if they have already solved the same problem before, that is, if they have already practiced the necessary procedure to reach the solution.

The same goes for remembering skills like swimming, typing with ease on a keyboard, or riding a bicycle. These are skills that, once learned, are no longer forgotten even when we fail to practice them for long periods of time. Maybe they “oxidize” because of lack of practice, but in a short time it is possible to recover the previous level of performance.

Viewed from this angle, human memory appears to be responsible for running very different tasks. However, this operation is not always performed satisfactorily. Some failures, like not remembering where we left our house keys, don’t seem to be very serious. In other situations, failure can seem worrisome, such as when we can’t remember who we just talked to.

What do we mean by memory?

Memory is the ability we have to learn, organize and fix events from our past and is closely linked to another basic psychological process: attention. Through memory we are able to store data through very complex mechanisms that are carried out in three steps: encoding, storage and recall. The presence of amnesia prevents this ability from developing properly.

We can define memory as the psychological process that serves to encode information, store it in our brain and retrieve it when the person needs it. Most importantly, this information acquired through learning can be retrieved when needed, sometimes with great speed and precision and at others with great difficulty.

Studies carried out in the field of cognitive memory psychology and cognitive memory neuroscience indicate that there are different memory systems in the human brain: each one with its characteristics, functions and processes.

The inability to access memories or learn something new

Amnesia is identified as a symptom when it is proven that someone has lost or has difficulty with memory. The person who has this symptom is not able to store or retrieve previously recorded information, either for organic or functional reasons.

Organic amnesia is related to some type of damage to an area of the brain, which can be caused by illness, trauma or the abuse of certain drugs. Functional amnesia, in contrast, arises from psychological factors, such as a defense mechanism (eg, post-traumatic hysterical amnesia).

There are also cases of spontaneous amnesia, such as transient global amnesia (TGA). This disorder is more common in older men and usually lasts for less than twenty hours.

Another type of classification is one that divides amnesia into two because of the memories the person cannot retrieve or form. Thus, we say that a person has anterograde amnesia when he is unable to form new memories. On the other hand, we say that a person has retrograde amnesia when he cannot recover memories that he previously could.

A person with anterograde amnesia can remember events that occurred in their youth or childhood, but they are unable to learn and remember events that occurred once the injury that caused the amnesia occurred.

Korsakoff’s syndrome

Among organic amnesias, Korsakoff syndrome is one of the most common clinical conditions; in fact, it forms part of their diagnostic criteria and is one of the most obvious and disabling symptoms. It gets its name because Korsakoff was the first person to describe this syndrome.

Korsakoff syndrome is characterized by an acute phase of mental confusion and spatiotemporal disorientation. In chronic stages, the state of confusion continues to exist. Often, the onset of this syndrome is the continuation of an episode of Wernicke’s syndrome (encephalopathy).

The main symptomatology of Wernicke’s stage consists of the presence of ataxia (lack of coordinated movements), ophthalmoplegia (paralysis of the eye muscles), nystagmus (involuntary movements of the pupils) and polyneuropathy (pain and weakness in different limbs).

People with Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome also suffer from disorientation of time, place, and person, inability to remember family members, apathy, attention problems, and inability to maintain a coherent conversation.

Retrograde amnesia: forgetting the past

A severe concussion of the brain as a result of a fall, an accident, or the application of electric shocks as a therapeutic method in depressed patients often causes retrograde amnesia. In many cases, amnesia seems to affect exclusively the minutes before the concussion. If it is too strong, the loss can affect memories formed in the months or even years before the time of the concussion.

Retrograde amnesia is thus defined as an inability to remember the past. In many cases, this type of amnesia usually disappears, so the person is able to gradually recover some of their memory. In the best cases, recovery is complete.

Anterograde amnesia. living without a future

There are cases in which a brain injury causes a global and permanent memory deficit without other intellectual damage. We call this “amnestic syndrome”. A person with “pure” amnesia retains their intellectual capacity intact, has no language problems, has no impairments in perception or attention, and retains skills acquired before the injury.

However, the amnesiac is characterized by a great difficulty in retaining new information (anterograde amnesia). These people are capable of carrying on a conversation. Their working memory works normally, although a few minutes later they are not able to remember what happened.

A person with this type of amnesia can’t learn new things (or has a hard time doing it) and sometimes can’t remember previous information either. It is as if the person lives eternally in the present. The past does not exist and the future can hardly be imagined without a past. About the amnesiac, it is said that he “lives continuously in the present”, that he cannot make plans for the future (because he forgets them).

Brain areas involved

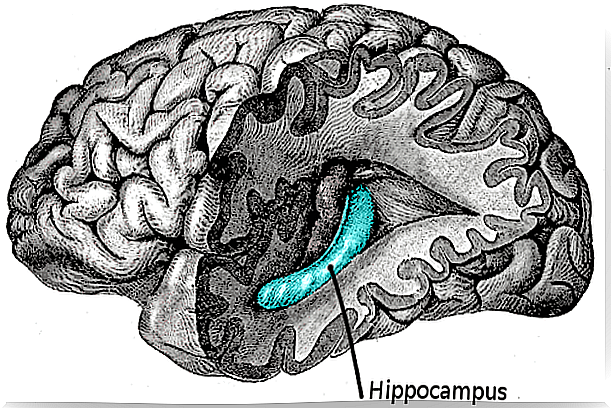

Determining which brain regions participate in the development of anterograde amnesia is one of the main challenges for current science. The brain damage that causes anterograde amnesia is generally believed to be located in the hippocampus and areas of the medial temporal lobe.

These brain regions act as a ticket where facts are stored provisionally until they are stored more permanently in the frontal lobe. Thus, the hippocampus is interpreted as a short-term memory store. If this region does not allow to store the information correctly, it will be impossible for the information to pass to the frontal lobe, making it impossible to store long-term memories. If the amnesia is not total, the memories will not have many real details.

However, despite the hippocampus apparently being the most important region of anterograde amnesia, recent studies have already indicated the participation of other brain structures in this process. More specifically, it is assumed that damage to the anterior basal brain could also impair the process. These regions are responsible for producing acetylcholine, a very important substance for the functioning of memory, as it initiates and modulates the processes of memory formation.

The most common form of basal anterior brain damage is aneurysms, a condition that has been associated with anterograde amnesia. Finally, the relationship between the changes in amnesia and Korsakoff syndrome established that a third region could also be involved in the development of anterograde amnesia.

This last structure is the diencephalon, a region that is highly compromised by Korsakoff syndrome. The strong relationship that exists between anterograde amnesia and Korsakoff syndrome has led to the study of the participation of the diencephalon in amnesic processes today.

The feeling of living outside the present time

The clearest evidence of anterograde amnesia is the poor performance of people with amnesia on traditional memory and recognition tests. In fact, a few minutes after being presented with a list of 15 or 20 words, the person with amnesia is unable to remember many of them.

In addition, the problem is more evident for words at the beginning or center of the list, while the latter are more remembered and for them the yield may be similar to normal. The same thing happens when it comes to a conversation, a movie or a television show. Everyday events are a problem: people with amnesia forget where they leave their things, what they’ve done, and the people they’ve met.

Because of this, they may have problems getting along with each other, as it is very difficult for them to carry on a conversation or remember what they talked about with another person in other situations. Furthermore, they have the feeling of living outside the present tense.

They talk about events and people from the past as if things happened just yesterday. They can’t plan for the future and don’t even know what they’re going to do tomorrow. Maybe that’s why they lack that warmth or that personal intimacy that we normally use in our references to the past and in our hopes for the future.

At the same time, it’s obvious that your memory problems can seriously disrupt your daily life. At home they may require constant care or supervision, as they are unable to remember to take a medication at set times, cannot learn to perform tasks that include many consecutive steps, etc.

However, people with anterograde amnesia can do other things. Some learn to take short trips, for example, from home to nearby stores. Much of their knowledge seems not to have been lost, as with retrograde amnesia.

Can people with amnesia learn new general knowledge?

Gabrieli, Cohen, and Corkin (1983) tried to find this out with patient HM, asking him to define custom words and phrases that had come into use when he was already amnesic. His success was limited, although he knew what “rock and roll” was. There was also an attempt to get him to learn the meaning of unfamiliar words. Despite quite a long training, he was barely able to correctly match the words with their definitions.

There are other cases. A 10-year-old child with severe anterograde amnesia due to anoxia (lack of oxygen) was unable to improve his reading level after the episode that caused the amnesia and did very poorly on several semantic memory tests. In comparison, she was able to learn to use computer games as easily as her peers (Wood, Ebert & Kinsbourne, 1982).

How is it possible to explain amnesia?

Some theoretical explanations have found the key in the existence of more than one memory system. While some of them remain intact in amnesia and are responsible for normal functioning in certain tests, another or other systems are damaged. Therefore, the performance in the different tests varies when compared to the income of the population that does not have amnesia.

The distinction between episodic memory and semantic memory (Tulving, 1972) was useful for some authors to support that in the amnesic syndrome, semantic memory functions normally. This would explain the conservation of linguistic functions. The damage to episodic memory would give way to failures in recall and recognition; a typical failure of these people.

The person with amnesia retains language functions intact and shows good performance in tests with words that require knowledge acquired in the past. In this sense, all the concepts and rules that are necessary to successfully solve these tests are acquired early in anyone’s life.

Leaving aside theories about how amnesia is acquired, the most important thing is to stick with the idea that anterograde amnesia is a selective memory deficit that occurs as a consequence of brain damage. The consequence of this is that the person has significant difficulties in storing new information. People who have this alteration are unable to remember new aspects and have great learning difficulties.

By contrast, anterograde amnesia does not affect recall of past information. In this way, all the information stored prior to the appearance of the alteration remains preserved and the person is able to remember them without problems. On the other hand, it must be taken into account that the characteristics of anterograde amnesia may vary in each case.

Bibliography:

Belloch, A., Sandín, B. and Ramos, F. (Eds.) (1995). Manual of Psychopathology (2 vols.) . Madrid: McGraw Hill.

Freedman, AM, Kaplan, HI and Sadock, BJ (Eds.) (1983). Treaty of Psychiatry. (2 vols.). Barcelona: Salvat. (Orig.: 1980).